Bottom Line Up Front

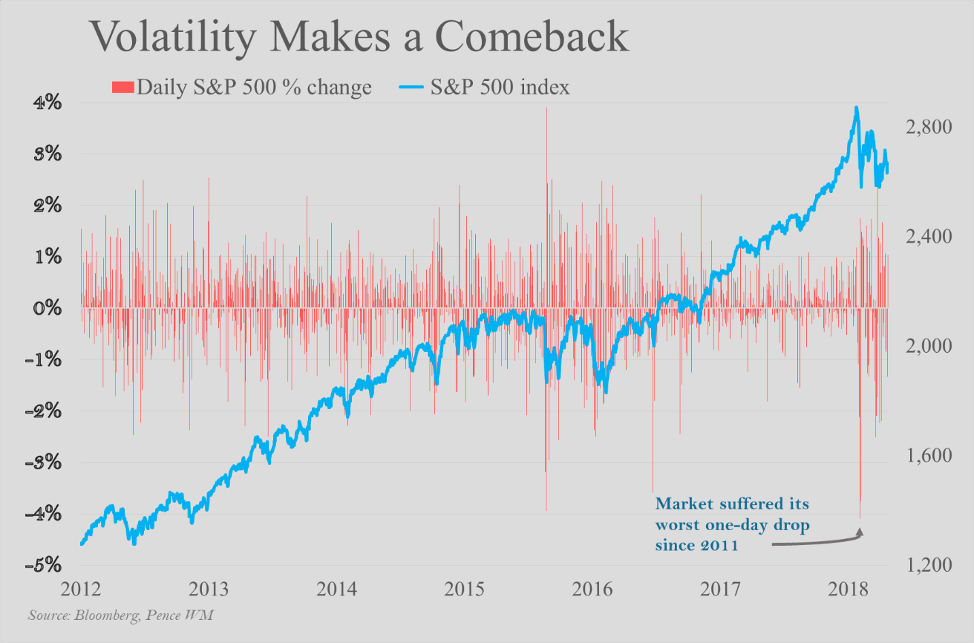

Corporate earnings are at an all-time high but headline news is creating volatility. The S&P 500 index has continued on its volatile path into the second quarter of 2018. As of April 26th, there have been 31 daily swings of at least 1% so far in 2018, up from 8 for the entire year of 2017 and relatively twice the frequency that occurred in the 2012 – 2016 market years (see chart below). Noise from trade friction between the US and China along with regulatory risks for technology firms such as the Facebook data scandal and Trump’s attacks on Amazon have all contributed to recent market volatility. Meanwhile, traditional fundamentals show us that the U.S. economy doesn’t look to be anywhere near a recession. In contrary, many economists have raised their GDP growth forecast for 2018 closer to a 3% rate, something we have not seen since 2005. Furthermore, projected corporate earnings growth in the first quarter since the passage of tax reform is expected to be the highest in eight years, according to FactSet. In times like this, it is important to separate noise from market fundamentals. The blue S&P 500 index line in the chart shows an upward trend despite all the noise. For the rest of the year, we continue to remain positive, but this is going to be a bumpy road.

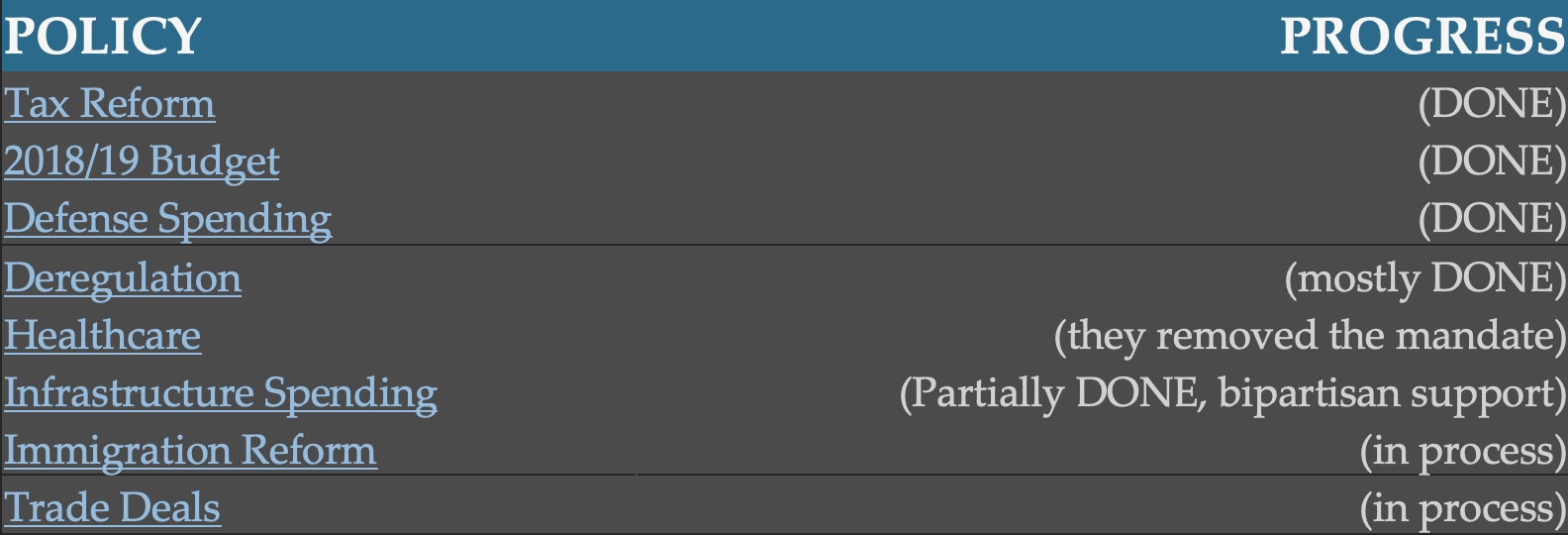

We stated in our 2018 Q1 Newsletter that the biggest risk to the stock market could be future political gridlock because of the midterm election in November 2018 where the Democratic Party will seek to regain congressional majorities and as a result may make future legislation challenging to pass. From an economic perspective, most of the Trump administration initiatives have been accomplished by Congress but it may take a while for them to fully manifested (see table below). From a market perspective, volatility may increase due to the fear generated by headline risk and political gridlock. At Pence Wealth Management, we are not overly concerned about gridlock because we have frequently had gridlock in Washington and both the market and the economy have moved forward during these years. Key policies that were expected to impact economic growth, corporate earnings and/or market volatility have already been either discussed or passed by Congress and signed by the President.

Immigration has been a touchstone of U.S. political debate for decades. Congress has been unable to reach an agreement on comprehensive immigration reform for years and we don’t expect them to get it done before the November election. Regarding trade deals, we view the recent escalation in tariff threats as negotiating tactics in an effort by the President to reduce the US trade deficit and expect the hyperbole to mitigate given the fact that China and other major trading partners have significantly more to lose than gain if the United States chooses to impose across-the-board tariffs. In fact, China’s President Xi Jinping has already made some concessions, including lowering tariffs on auto imports from the U.S., improving protection of intellectual property, and allowing full foreign ownership of Chinese automobile companies within five years. Until now, foreign automakers were not allowed to own more than 50 percent of manufacturing efforts on Chinese soil.

Tensions have also eased on the Korean peninsula and, for now at least, the risk of war has diminished. On April 20, North and South Korea announced that they established for the first time a direct telephone line between their leaders. The test call “went smoothly” and lasted four minutes and 19 seconds, said Youn Kun-young, director for South Korea’s government situation room. “It was like I was calling from next door,” Mr. Youn said. President Trump and Kim Jong Un are slated for a late-May to early-June Summit, which promises to be one of the larger events of this quarter. The most recent meeting, April 27, of the leaders of North and South Korea indicate that there may be an official end to the war that started in 1950.

Market Report

The biggest determinant of market performance is earnings. In 2018, we see continued earnings growth to move the market forward. However, we also believe volatility will limit market performance to less than its potential.

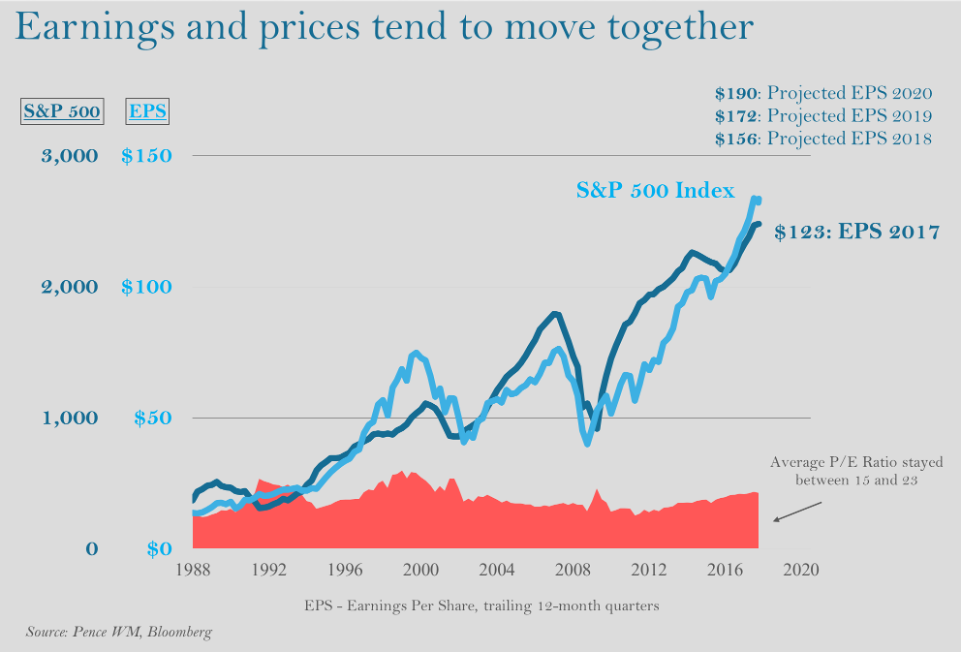

Over the past 30 years, corporate earnings have been the main driver of market performance (see chart below). Both the S&P 500 index and its earnings have moved together 93% of the time since 1988. Meanwhile, the Price-to-Earnings multiple (P/E Ratio)— calculated by dividing the S&P 500 index by its Earnings Per Share (EPS)—has mostly remained between the range of 15 and 23, averaging 19 during the same period (red area in chart).

According to Bloomberg data, 2018 projected earnings are expected to increase to over $150 per share from $123 in 2017, partly thanks to the Tax Reform legislation which passed in December 2017. We believe continued slow but steady economic growth in the US and overseas, a tightening labor market, and strong aggregate demand will push EPS higher above $200 per share by 2021.

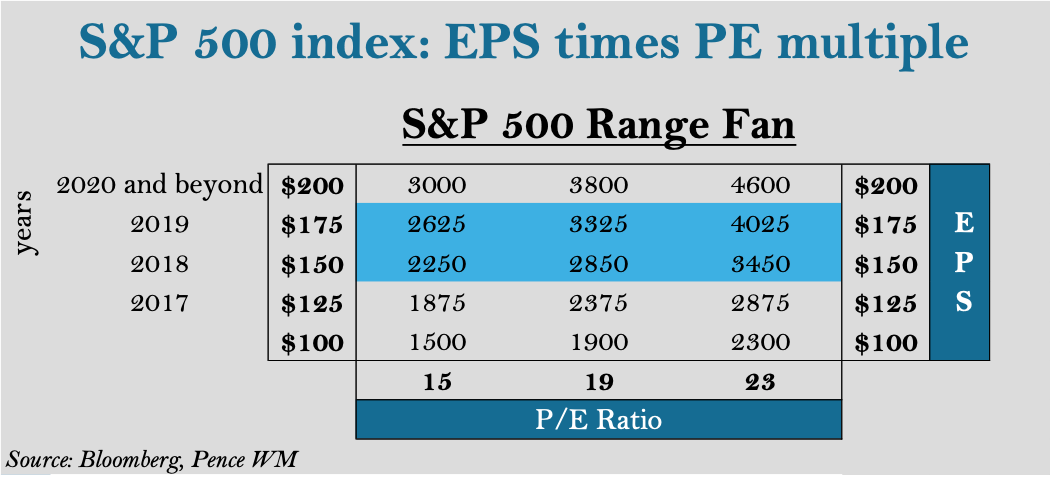

Historically, given the positive relationship between earnings and the S&P 500 index, we expect higher earnings will continue to lead the market higher, with some volatility. The table below demonstrates possible values of the S&P 500 index under various combinations of EPS and P/E Ratio.[1] In spite of what could be a very volatile market between April 27 2018 and December 2019, we expect that market to end 2019 somewhere in the range of 2625 (down 2%) and 4025 (up 51%).

Estimating the future value of the market multiple is a difficult task. We can only use historical data to calculate its possible range. One thing we could predict is that, historically, P/E Ratio tends to move towards the upper end of its range when investor and business confidence are high; conversely, it tends to move to its lower range when uncertainty emerges, either political or economic. Estimating corporate earnings is a relatively easier task because most companies provide reports on their general outlook. Given the expected boost in earnings due to tax reform along with synchronized global growth and strong aggregate demand, corporate earnings reports suggest we are on track for another positive year for the market, all else being equal.

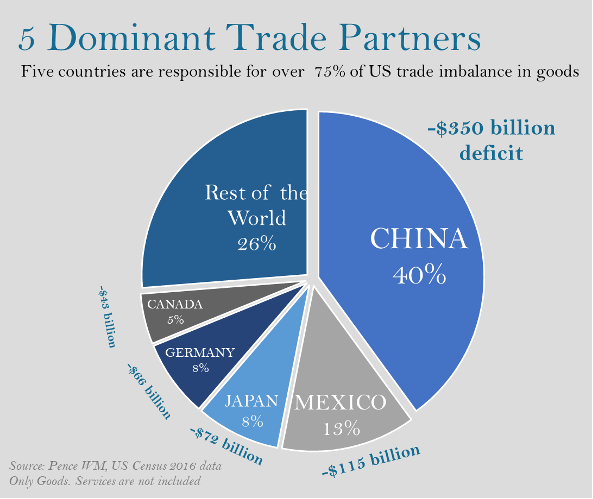

Trade Tensions

A trade deficit occurs when a nation imports more than it exports. For instance, in 2017 the United States exported $2.3 trillion in goods and services while it imported $2.9 trillion, leaving a trade deficit of roughly $600 billion. Services, such as tourism, intellectual property, and finance make up roughly one third of exports ($778 billion), while major goods exported include aircraft, medical equipment, refined petroleum and agricultural commodities. Meanwhile, more than 80% of imports are goods, dominated by capital goods, such as computers and telecom equipment; consumer goods, such as apparel, electronic devices, and automobiles; and crude oil. (The deficit in goods, at $866 billion, is higher than the overall deficit since a portion of the goods deficit is offset by the surplus in services trade.) [2]

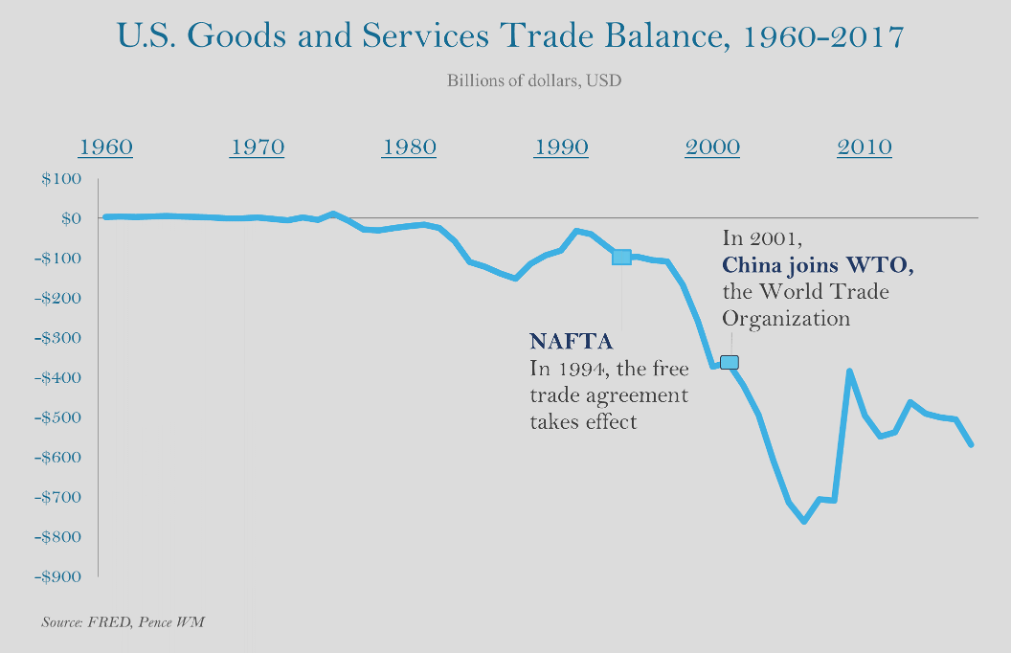

The United States nearly had no trade deficit before 1980. Since 2000, the deficit has averaged $540 billion. It peaked over $760 billion in 2006 and was $568 billion in 2017, roughly 2.8% of its GDP (see chart below).

President Trump has made reducing the US trade deficit a policy priority, blaming trade deals like North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and confronting China for theft of America’s intellectual property rights and unfair trades as well. The United States Constitution gives Congress the power to impose and collect taxes, tariffs, duties, and the like, and to regulate international commerce. However, over the years, Congress has given its authority away to the executive branch, the President.

There is substantial debate over how much of the trade deficit is caused by foreign governments as well as what policies, if any, should be pursued to reduce it. Most economists generally see factors such as government spending, a strong dollar, or steady economic growth more important than trade policy in determining the overall deficit.

The fundamental cause of a trade deficit is an imbalance between a country’s savings and investment rates. As Harvard’s Martin Feldstein explains, the reason for the deficit can be boiled down to the United States as a whole spends more money than it makes, which results in a current account deficit. That additional spending must, by definition, go toward foreign goods and services. Financing that spending happens in the form of either borrowing from foreign lenders (which adds to the US national debt) or foreign entities investing in US assets and businesses—the capital account. [3]

President Trump, who campaigned on ending trade imbalances, argues that “trade deficits hurt the economy very badly.” He blames “horrible deals” with Mexico, South Korea, and other countries for allowing too many cheap foreign imports that have put American factories out of operation and “destroyed jobs.” The administration has made lowering the deficit with Mexico a priority in its current renegotiation of NAFTA.

The most common argument is that the United States has a history of assisting other nations to rebuild their economies in times of political strife or humanitarian crises, and decades later it no longer needs to subsidize what are now developed economies. After World War II, leaders in Washington understood that the United States had a powerful strategic interest in helping Western Europe to recover and stand on its own. Under Secretary of State George C. Marshall, the United States worked to rebuild post-war Europe with the Marshall Plan. This involved investing approximately $22 billion in Europe’s redevelopment— or roughly $182 billion in real 21st-century dollars adjusted for inflation. The United States also provided grants and credits to Japan, China, and other Asian countries. Altogether, the total of American grants and credits to the world from 1945 to 1953 came to $44.3 billion—or roughly $365 billion in today’s dollar. [4]

Today, almost all politicians would agree that the Marshal Plan was a success. The world has democracy across Europe and Japan is the world’s third largest economy and one of America’s most important allies in the Asia-Pacific.

With regards to China, the Trump administration claims that the United States mistakenly supported China’s membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 on terms that have failed to force Beijing to open its economy. During the 15 years of negotiations leading up to 2001, the United States and other countries set several conditions for China’s admission, including an extensive series of liberalization commitments. These involved concessions such as dropping tariffs on many categories of goods, opening up agricultural trade, and allowing in foreign service providers. In contrast, the United States did not need to make any new market-opening concessions; it just needed to guarantee that it would offer China most-favored-nation status. [5]

On April 3rd, the Trump administration published a list of some 1,300 products it proposes to hit with tariffs of 25% on $46 billion of Chinese imports, on top of the steel and aluminum tariffs imposed in March. Just a day later China produced its own list, covering 106 categories. President Trump further upped the ante by threatening tariffs on another $100 billion of Chinese imports.

We view this escalation as a negotiating tactic. Both countries’ lists are, for now, no more than threats. Over the next month America’s list will be open for public consultation (there is no deadline for the tariffs to come into force). China has said that it will wait for America to move. There is still a very good chance the two sides will choose new negotiation rather than a trade war.

One of the most powerful laws in economics is the law of “unintended consequences”, which was originally formulated by American sociologist Robert Merton. According to a Bloomberg Businessweek study, the proposed tariffs on imports from China may hurt other nations or even American companies because one-third of China’s gross exports consisted of value that was added outside of China (see table below).

Back in 2002, President George W. Bush placed tariffs on imports of certain steel products in an attempt to protect the domestic U.S. steel industry from foreign dumping. The rates ranged from 8% to 30% on certain steel product imports from all countries except Canada, Israel, Jordan, and Mexico. In the end, the effects of higher steel prices, largely a result of the steel tariffs, led to a loss of nearly 200,000 jobs in the steel-consuming sector, a loss larger than the total employment of 187,500 in the steel-producing sector at the time. [6] President George W. Bush’s tariffs didn’t last very long. They were lifted by Bush after a year and half on December 4, 2003.

China’s threat of an additional 25% tariff on US-produced cars would hurt neither General Motors nor Ford—they both have joint-venture factories in China—but it would harm the German companies that produce most American-made cars sent to China. Estimated 2018 revenue from cars built in the US and sent to China:

- BMW, $3.9 billion

- Daimler, $3.1 billion

- Tesla, $2 billion

- Ford, $0.6 billion

- Fiat Chrysler, $0.3 billion

In mid-April, China’s international trade representative held a series of meetings with the ambassadors from major European nations to ask them to stand together with Beijing against U.S. protectionism. Some of the western diplomats involved in the meetings have viewed the approaches as a sign of how anxious Beijing is getting about the expanding conflict with Washington.

Knowing that it has more to lose than the US, China is proposing tariffs on industries in politically important states that would get the president’s attention. The BBC’s Paul Blake explains that it’s all about politics and hitting politicians where it hurts the most, their constituency.

Iowa is famous for farming, especially for their soybean, corn, and livestock. The Iowa caucus also holds the first presidential nomination contest and has an outsized impact on US politics as one of the most inconsistent swing states (the 2000 and 2004 elections were decided by margin of .3% and .6%, respectively). In the 2016 election, Iowa switched its electoral preference from Democrat to Republican. If the state’s economy goes south, its populace is more likely to switch back to the Democrats in the next election.

Car manufacturers in Michigan as well as orange crop producers in Florida were feeling the impact from China’s retaliation. These three states have key governor races in the November election. They also have a number of competitive House of Representative races which may determine whether Republicans maintain control of US Congress. Wisconsin, Speaker Paul Ryan’s state is home to Harley Davidson motorcycle while Kentucky, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnel’s state is home to American bourbon—both targets of Chinese tariffs.

Although we believe the United States should renegotiate its trade deals and make sure it gets a fair deal with its trading partners, there are no clear winners from a bilateral trade war. Both China and the US lose and it doesn’t matter if the US suffers proportionally smaller losses than China because US consumers will still be worse off than they were before. According to a Goldman Sachs study, a 10% across-the-board tariff improves the US trade balance by $40 billion in the first year and almost $100 billion after the third year, assuming no retaliation. With retaliation, however, the benefit of the same tariff is limited to $20 billion after the first year as both imports and exports fall sharply. The US economy goes into a stage of higher inflation, interest rates, a stronger dollar, and tighter financial conditions.

We haven’t had a full-blown trade war in over 90 years for many good reasons. Countries understand the devastation that can result. At this point, we believe the evidence suggests that the situation won’t deteriorate further from a trade spat to a trade war. For example, shortly after the announcement, both Canada and Mexico were exempted from the US steel and aluminum tariffs; in addition to 28 countries in the European Union along with Australia, Argentina, Brazil, and South Korea—not exactly the mark of a trade war but rather the result of what ultimately looks like hardline posturing.